By Dr Nina Hood

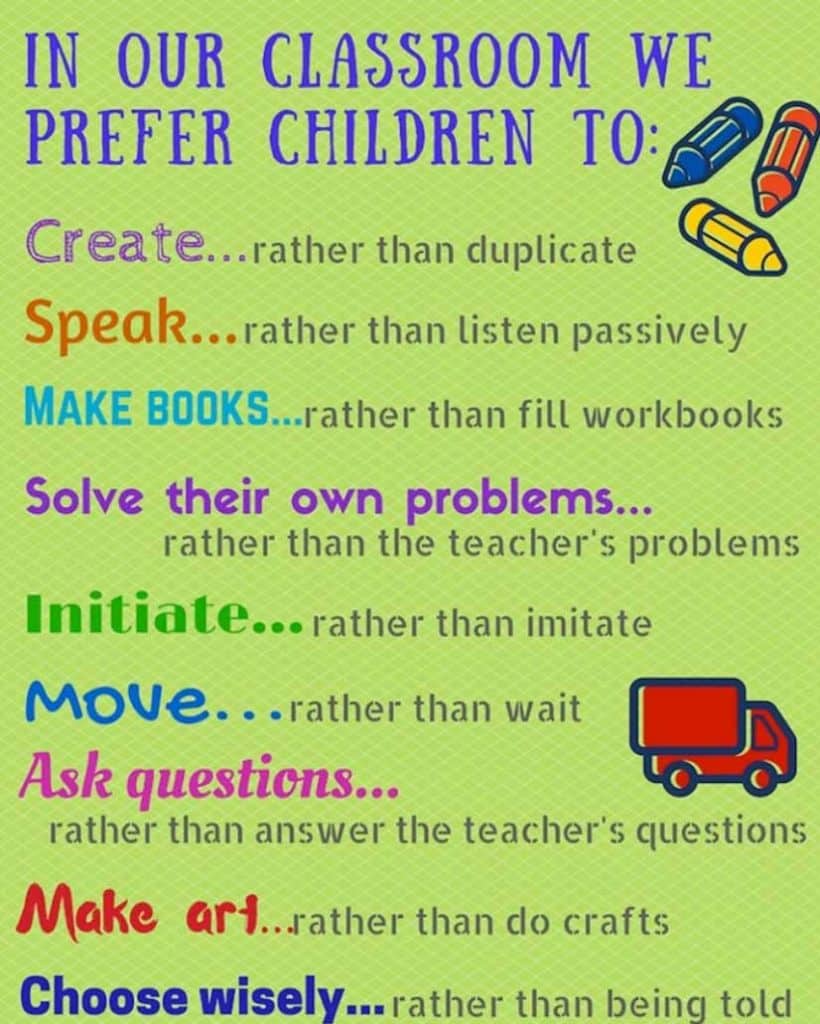

I came across this image on social media recently. Reading it reminded me of how education is full of statements, which on the surface seem to make intuitive sense. However, when we stop and think about their implications, their plausibility quickly diminishes.

Firstly, it falls into the trap, so often found in education, of promoting binary thinking. Rather than seeing education and teaching and learning as a fluid continuum where different activities are relevant and meaningful at different times, it presents an all or nothing approach. Secondly, many of the ideas presented have no basis in what the research evidence tells us is effective for supporting students’ learning.

Speak rather than listen passively.

At The Education Hub we are big supporters of oral language or as it sometimes is known, oracy. We’ve created resources for ECE teachers on the importance of talk, and one of our Bright Spots Awardees is developing an oracy curriculum for Years 0-6. However, we would argue that listening (actively rather than passively) is not the opposite of speaking but rather is an integral part of oral communication. Students needed to be supported to listen actively and carefully, as this is a critical component of participating in discussion and dialogue, and in dialogic teaching and learning.

Initiate rather than imitate

While developing students’ ownership of their learning is hugely powerful, this does not discount the important role that imitation can play in learning and development. Imitating the behaviour, actions and language of others is a pivotal component of early learning. Furthermore, adults can strengthen this learning interaction by imitating the actions and language of young children in a dialogic interplay. The importance of imitation in learning does not end in childhood. The apprenticeship model, whereby the novice learns from the master and gradually increases their knowledge and expertise, is another form of imitation. There is a considerable body of research supporting the power of the apprenticeship model of learning.

Solve own problems rather than the teacher’s problems

While it is sometimes appropriate for students to pose and solve their own problems, this does not discount the instructional potential of teacher created problems. It can take considerable existing knowledge of a topic and expertise to pose relevant problems that have the appropriate level of challenge and will lead to the types of thinking and learning we are seeking. By only asking students to pose and solve their own problems we run the risk of limiting their learning by not exposing them to new topics and ideas, or extending their thinking.

Make art rather than do crafts

This statement seems to reinforce the historical hierarchy that positioned the “fine arts” (painting, drawing, sculpture) above traditional “crafts” (sewing, embroidery, pottery etc). It is worth noting that, particularly across the twentieth century, artists tried to dismantle this division. Consider for example Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party, which among other things utilised traditional female crafts and elevated them to the status of high art. Or the Dadaists who incorporated found objects into their artworks. Or the Pop artists who elevated the subject and methods of comic books and advertising in their art. Crafts can require just as much knowledge, expertise and creativity as art. It is less about the label we give an activity and more about how it is structured, the expectations established around it, and the processes that are being utilised in relation to the desired learning outcomes.

Ask questions rather than answer the teacher’s questions

Encouraging students to ask questions is something that nearly all teachers would embrace as a positive enterprise. However, this does not discount the powerful learning that can arise from effective teacher-led questioning. Carefully constructed questioning helps students discover, evaluate and apply content, and leads to better long-term recall. When teachers ask higher order questions that encourage sustained dialogue, it is an intellectually stimulating and engaging activity. Research has shown that effective questioning enables teachers to extend students’ learning and create new connections between ideas, as well as develop rich opportunities for collaboration, problem-solving and critical thinking.

Two key messages emerge from the unpacking of these statements. The first, is that there is an attempt from some in education to downplay the pivotal role that teacher knowledge and expertise plays in education and in the creation of rich and powerful learning opportunities. The second, is that it matters less whether a particular instruction technique is present and more how, when and for what purpose a technique is used.