‘Teachers with high sense of efficacy create mastery experiences for their students whereas teachers with low instructional self-efficacy undermine students’ cognitive development as well as students’ judgements of their own capabilities.’

(Frank Pajares)[i]

Teacher efficacy is a form of self-efficacy and is a powerful predictor of teaching performance. A teacher’s sense of efficacy is important because teachers need to feel competent and confident in their ability to teach and reach all students. Self-efficacy has become an important framework in education to predict and explain the perceptions and judgements that influence teachers’ decisions and actions in the classroom. Wyatt defines teacher efficacy as ‘Teachers’ beliefs in their capabilities of supporting learning in various task and context-specific, cognitive, metacognitive, affective, and social ways’. [ii]

How does self-efficacy develop in teachers?

Teacher efficacy begins to develop early in teaching careers. While teacher efficacy beliefs are malleable in the early years of teaching, they tend to become more rigid and resistant to change once teachers have ample mastery experience (actual teaching experience) to fall back on. However, teacher efficacy does not develop linearly, and the acquisition of complex teaching skills and knowledge happens in flux over time before teachers reach stable levels of self-efficacy. Studies have indicated that factors such as the availability of teaching resources and the level of interpersonal support received from school leaders, colleagues, parents and the wider community affect the levels of self-efficacy of novice teachers more than their more experienced colleagues, while mastery experience seems to play a greater role in the higher levels of self-efficacy of experienced teachers.

Teacher efficacy develops from a combination of mastery experience, vicarious experience, social persuasion, and physiological and emotional states. Mastery experience, the most powerful source of self-efficacy, develops through past successful accomplishments. For a primary school teacher of science, for example, these accomplishments might include positive out-of-school and in-school science-related experiences during their own school years as well as opportunities during their teaching career to conduct science-based workshops and deliver presentations about primary science. Mastery experience might also include their resourcefulness as teachers of primary science, their engagement in continuous related educational and professional development opportunities and their effective utilisation of instructional time in the classroom.

Vicarious experience, the second most powerful source of efficacy, is attained through what teachers observe, hear and read. Teacher efficacy is strengthened when teachers observe effective instruction by their peers. It is particularly effective if teachers are able to observe peers with a similar level of experience and proficiency. Observation of proficient peers who deliver effective instruction in person or on film can strengthen a teacher’s belief in their capabilities to teach in similar ways. Critiquing their own teaching performances on film or video-tape footage (self-modelling) is another powerful strategy for developing teacher efficacy, as is visualising oneself teaching in a future situation (cognitive self-modelling).

Social persuasion also has a strong influence on teacher self-efficacy. Sincere and genuine feedback from supportive school leaders and colleagues, parental acknowledgement of teacher performance, and student displays of enthusiasm in their learning are all forms of social persuasion. Teacher efficacy also develops through positive interpretations of physiological and emotional states. For example, when teachers experience feelings of excitement prior to introducing a new topic, or feelings of pleasure and satisfaction from the delivery of a successful lesson, their self-efficacy is boosted.

What does a self-efficacious teacher look like?

Self-efficacious teachers model self-efficacy. They are intrinsically motivated, open-minded, innovative and curious, and demonstrate competence and confidence in their ability to perform actions that lead to positive student outcomes. Research has shown that self-efficacious teachers:

- value the importance of continuous intellectual development and use critical reflection to consistently improve their teaching practice. They actively seek ongoing professional learning, keep abreast of wider educational issues and changes, and capitalise on enhanced teaching and learning opportunities. They treat less familiar learning areas as a source of their own development.

- set attainable goals that influence the teaching decisions they make, and weigh up the magnitude of tasks in relation to the skills and knowledge they possess.

- establish supportive classroom climates and exert extra effort to ensure every student feels successful by designing meaningful learning experiences for them. They create learning environments where their students know their teachers believe in them every step of the way.

- foster student growth in deeper learning, welcome student error and willingly experiment with new teaching strategies to enhance student outcomes. They employ learner-centred strategies such as inquiry, project and collaborative experiences, sharing control of learning with their students through activities that promote rich peer discussion and negotiation. They maintain strong academic focus throughout lessons and provide constructive feedback to students.

- do not become disenchanted through difficult teaching periods and retain a positive sense of job satisfaction as professionally committed educators. When faced with trying circumstances in their teaching careers, self-efficacious teachers demonstrate resilience, viewing knockbacks as temporary stumbling blocks.

What is the impact of teacher self-efficacy on student outcomes?

Research has shown that teacher efficacy influences student outcomes. For example, assured levels of teacher efficacy positively correlate with increased academic achievement, student motivation, and increased levels of student self-efficacy. In the primary years, students with self-efficacious teachers have been found to be more engaged in the classroom and interested in their learning, whilst at high school, students with self-efficacious teachers have been observed to display more on-task behaviour, increased engagement, effort and intrinsic motivation for school, more positive attitudes towards learning, and better opinions about their teacher.

How can teachers be supported to develop self-efficacy?

Hawe and Dixon emphasise the role of school leaders and professional learning facilitators in building self-efficacious teachers, and encourage them to consider six key criteria:[iii]

- the development of philosophical understanding of education (the goals, forms, methods and meaning of education)

- the development of pedagogical content knowledge (the integration of subject expertise and skilled teaching of that particular subject)

- teacher engagement from both teachers’ and learners’ perspective (the ability to engage as a learner in the classroom and show empathy for the student’s perspective as a learner)

- reflection on learning within different contexts both as a teacher and a learner

- the examination of deep-seated beliefs and values and how each of these might permeate teachers’ day-to-day actions and consequential construction of students’ identities as learners

- the development of teacher competence and confidence in implementation of strategies to bring about desirable effects for learners (through Bandura’s four sources of efficacy: mastery experience, vicarious experience, social persuasion and the interpretation of physiological and emotional states).

It is imperative that the professional learning offered to teachers as learners is positive, supportive, collaborative, and trusting to maximise their risk-taking opportunities within the learning.

Reflective questions for teachers

The following questions will help you reflect on your own self-efficacy and consider the support you might need from others to help you build your self-efficacy or better support the self-efficacy of your colleagues and students.

- How have Bandura’s four sources of influence (mastery experience, vicarious experience, verbal and social persuasion, and physiological and emotional states) helped to develop your self-efficacy over time in different learning areas:

- In your early school years?

- In your later school years?

- As a practising teacher?

- In what ways do you believe you transfer your own values, positive attitudes towards learning and learning experiences to your students?

- How much can you help other teachers with their teaching skills?

- What professional learning do you think will further build your self-efficacy as a teacher?

- What actions do you take to promote innovation and creativity among students?

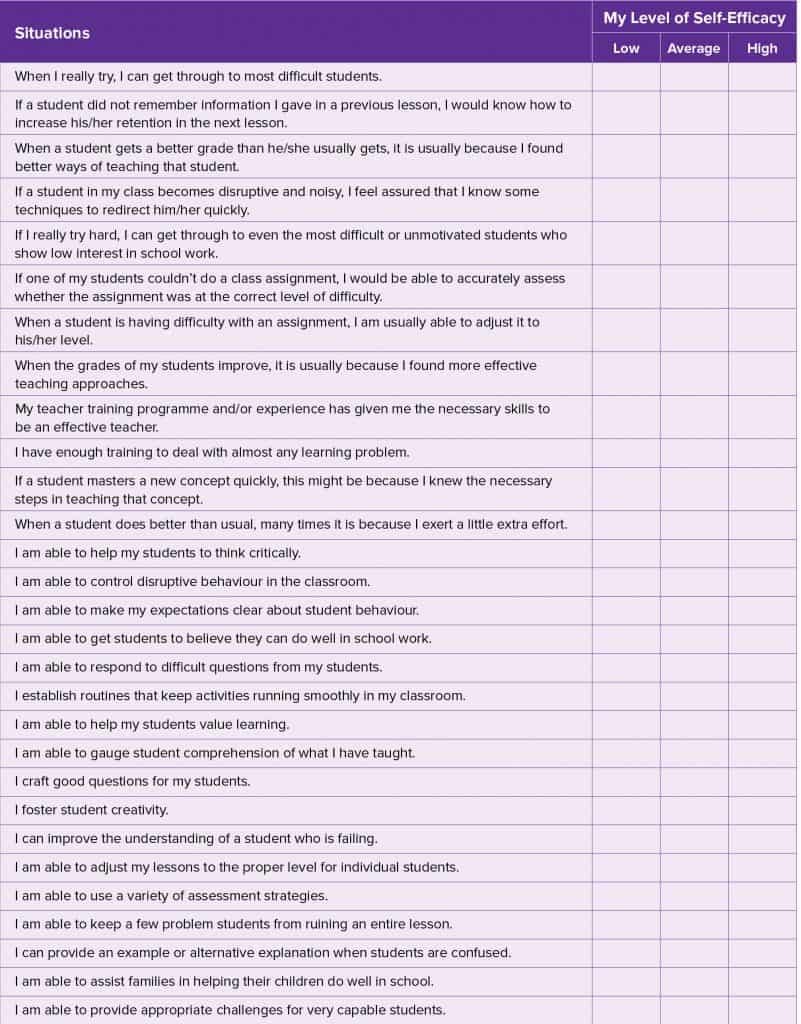

Using Gibson and Dembo’s Teacher Efficacy Scale [iv], how would you currently rank your teacher efficacy in the following areas of teaching and learning – low, average, or high?

Coladarci, T. (1992). Teachers’ sense of efficacy and commitment to teaching. Journal of Experimental Education, 60(4), 323-337.

Poulou, M. (2007). Personal teaching efficacy and its sources: Student teachers’ perceptions.

Educational Psychology, 27(2), 191-218. doi: 10.1080/01443410601066693

Zee, M., & Koomen, M. Y. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 981-1015. doi: 10.3102/0034654315626801

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215. doi: 0.1016/0146-6402(78)90002-4

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Longman.

Gibson, S., & Dembo, M. H. (1984). Teacher efficacy: A construct validation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(4), 569-582. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.76.4.569

Hawe, E., & Dixon, H. (2015, May). Assessment for Learning as a catalyst for changing teachers’ understandings and beliefs: An experiential approach to learning and teaching in higher education. Paper presented at the International Conference: Assessment for Learning in Higher Education, Hong Kong.

Pajares, F. (2002). Self-efficacy beliefs in academic contexts: An outline. Retrieved from https://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Pajares/efftalk.html

Pintrich, P. R., & Schunk, D. H. (1995). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Schunk, D. H. (1991). Self-efficacy and academic motivation. Educational Psychologist. 26(3&4), 207-231.

Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–22.

Tschannen-Moran, M., & McMaster, P. (2009). Sources of self-efficacy: Four professional development formats and their relationship to self-efficacy and implementation of a new teaching strategy. The Elementary School Journal, 110(2), 228-45. doi: 10.1086/605771

Woolfolk, A. E., & Hoy, W. K. (1990). Prospective teachers’ sense of efficacy and beliefs about control (Motivation and Efficacy). Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 81-91. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.81

Woolfolk Hoy, A., & Burke Spero, R. (2005). Changes in teacher efficacy during the early years of teaching: A comparison of four measures. Teaching and Teacher Education 21(4), 343–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2005.01.007

[i] Pajares (2002), p. 23.

[ii] Wyatt (2014), p. 603.

[iii] Hawe & Dixon (2015).

[iv] Gibson & Dembo (1984).

By Helen Withy