Neurodiversity is a term used to describe neurological differences in the human brain. From this perspective, the diverse spectrum of neurological difference is viewed as a range of natural variations in the human brain rather than as deficits in individuals. These differences are often diagnosed as neurological conditions such as acquired illness or brain injury, autism, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), dyslexia, Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD), intellectual disability, and Tourette syndrome. For a detailed overview of the neurodiversity approach to disability, see An introduction to neurodiversity and neurodivergence.

The concept of neurodiversity embodies a strengths-based modelthat shifts the focus away from the challenges of students with neurological differences in favour of finding ways to work with the strengths of the student to enable them to participate and experience educational success. In this model, the strengths and interests of the student are the starting point for curriculum design, teacher pedagogy, and the design of the learning environment.

This resource provides strategies and information for working with students across the broad range of neurodiversities, and their diverse learning strengths and needs. The strategies and information discussed in this resource are intended to provide a starting point for teachers and highlight important considerations when working with neurodivergent students. All students have individual learning strengths and needs, which means that any strategies suggested in this resource will need to be adapted to suit the needs of the student.

Curriculum design

In order to apply a strengths-based model, it is important to know how to identify a student’s strengths and how to use those strengths when designing learning activities and learning goals. It may also be necessary to differentiate and adapt the curriculum for neurodivergent students.

There are two kinds of strengths that can be identified – strengths that the teacher recognises in the student, and strengths that the student recognises in themselves. These two may not always align, so it is important to consider each kind of strength when designing learning goals and activities. For example, a student in Year 6 may have a strong interest or self-perceived strength in reading but be reading books that are below the expected Year 6 level, while the teacher may identify that that same student has an above average ability in statistics while the student has little enthusiasm to engage with or complete work in this topic. The challenge for teachers of neurodivergent students is to find motivating topics that will engage the student while also allowing them to experience success in their learning. One way to do this is by creatively drawing on other strengths or interests to engage the student in the less favoured topic: for example, the teacher in the case above might leverage the student’s enthusiasm for reading to help engage and extend them in statistics.

Curriculum differentiation and adaptation

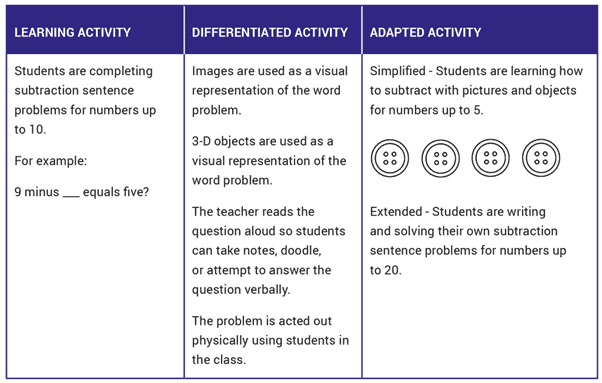

Differentiation and adaptation are strategies that acknowledge that the curriculum is not a one-size-fits-all model. However, the curriculum can and should be for all students. Differentiation or adaptation of the curriculum may be necessary in order to ensure that all students are able to access what is being taught and participate fully in learning activities. From a neurodiversity perspective, curriculum differentiation is a strategy that will allow all students to learn the same information in ways that best suit their learning needs. Where students are learning below or above the level of their peers, the curriculum can be adapted to pitch the learning at a level appropriate to the student or students. The table below provides an example of differentiation and adaptation in practice.

Table 1: Example of differentiation and adaptation in practice

Curriculum adaptation and differentiation may also occur through the use of multiple learning stations, where the same task is presented and can be performed in a number of ways. It is important to consider how curriculum differentiation may benefit the learning of all students, not just those who are neurodivergent.

Teacher pedagogy

In order to meet the needs of diverse learners, teachers often need to consider a range of ways to present information. Differentiated instruction involves thinking and being flexible about how to teach, and thinking about how to teach the same ideas and content differently, rather than always teaching certain subjects in a specific way. Differentiated instruction, alongside a differentiated or adapted curriculum, allows students to process information in a mode and at a pace that works for them. For example, some students may struggle to process information in large groups and need small group instruction, 1:1 follow up, or to work with a peer in order to process and understand the information that is being presented. Some students may have trouble listening when the teacher is talking and moving at the same time, while others may be the opposite and tune out when the teacher is talking while sitting still.

It is important that teachers get to know the students in their classroom and are aware of any characteristics of potential underlying neurological differences that may affect how they process information when it is taught in specific ways. The characteristics of common neurological differences that have implications for teacher instruction can be broken down into the following categories: cognition, social and emotional needs, and sensory needs. The following considerations may help to differentiate instruction in order to respond to the differing needs of neurodivergent students. In all cases, it is important to communicate responsively with students and, where appropriate, ask them what they need support with.

Cognition

These strategies will help attend to the needs of students with specific cognitive needs to do with information processing, memory, and organisation:

- Have a clear outline and learning objective for each lesson and communicate this to the class both verbally and visually

- End each lesson by reviewing the learning objective and allowing students to evaluate their own progress

- Have shorter, fast-paced, and interactive learning activities for students who are active in body and mind

- Be flexible about the time allocated to completing a task for students who require longer processing time or worry about getting things right

- Use colour coding to organise information

- Use a clear sans serif font that is 12pt or above, and black or blue markers that are easy for students to read

Social and emotional needs

These strategies will support students who find social interaction challenging or who have specific emotional needs:

- Encourage and facilitate social interaction between students

- If a student struggles with social interaction, consider letting them choose who they sit next to or engage in group work with

- Implement a buddy system for students who require prolonged social support

- Talk about and provide opportunities for students to practise appropriate social skills

- Provide safe opportunities for students to request help

- Communicate clear expectations

- Provide exemplars of work that is not perfect

- Be aware of signs that may indicate a student is becoming overwhelmed and respond with reassurance and compassion

Sensory needs

These strategies are designed to help meet the needs of students with specific sensory needs such as a sensitivity to noise or certain textures, or the need to be physically active:

- Be aware that some students may be particularly sensitive to some sensory information such as sound, sight, touch, taste, balance, and body awareness (temperature or pain)

- Acknowledge that some students find it difficult to process information when there is either too much or not enough noise in the room

- Consider allowing students to wear headphones or earplugs while they work, or create a quiet space for students who prefer to work in quiet

- Be aware of your own volume when speaking as well as the level of background noise in the environment

- Provide movement breaks for students who benefit from being physically active or find it hard to stay still for long periods of time

- If a learning task is particularly messy or involves certain textures that may cause discomfort for some students, consider alternative tasks that will allow the student to participate and achieve the learning objective

The learning environment

Differentiation in both curriculum design and teacher pedagogy are more likely to be effective when the learning environment is designed to support the implementation of differentiation. It is important to consider how assistive technology and the physical learning space or place where learning is occurring can be used to support neurodiverse learners.

Assistive technology

Some students may have assistive technology funded through the Ministry of Education to help them participate and learn. Assistive technology is a tool that can be used to remove barriers to learning for individual students. When integrated into the learning environment, assistive technology is something that may benefit the learning of all students. For example, students can read a book on a device or in print either individually or as part of a group activity. There are also options to listen to the book, with each word highlighted as it is being read allowing students to visually track what they are listening to. Follow up activities allow students to test their comprehension and practise what they have just learnt. There are many applications and websites that can be accessed for free and utilised in the learning environment to address diverse learning needs, such as Sunshine Online, Clicker, talk-to-text or text-to-speech, Math Ref Free, and IXL (mathematics and literacy).

Physical learning space

The physical learning space can be adapted to suit the needs of diverse learners through, for example, the layout of furniture, labelling the environment and resources, and considering the proximity of seating to potential distractions such as windows, doors, or other students. Try to provide a classroom environment that is clear visually and in physical layout to help diverse learners navigate movement from one area to the next. For example, colour code and label different areas of the classroom, and match colours and labels to resources intended for use in those areas. Teachers may also want to consider providing choice for where students work. Not all students like to work at tables or desks, and some prefer to work on the floor. Some students may benefit from learning in other environments, such as in the library, gym, or outdoors. With some modifications and creative thinking, most learning activities can be taught outside of the classroom, so consider how to use other areas of the school as places for learning.

References

Armstrong, T., & Ebrary, Inc. (2012). Neurodiversity in the classroom strength-based strategies to help students with special needs succeed in school and life. ASCD.

Armstrong, T. (2017). Neurodiversity: The future of special education? Educational Leadership, 74(7), 10-16.

Hendrickx, S. (2009). The adolescent and adult neuro-diversity handbook: Asperger’s Syndrome, ADHD, dyslexia, dyspraxia and related conditions. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Jena, S. (2013). Learning disability: Theory to practice. SAGE Publishers.

Lerner, J., & Johns, Beverley H. (2015). Learning disabilities and related disabilities: strategies for success. Cengage Learning.

Mirfin-Veitch, B., Jalota, N., & Schmidt, L. (2020). Responding to neurodiversity in the education context: An integrative review of the literature. Donald Beasley Institute.

Ottinger, B. (2003). Tictionary – A reference guide to the world of Tourette Syndrome, Asperger Syndrome, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder for parents and professionals. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

By Julie Skelling