By Dr Nina Hood

I recently read Russell Bishop’s latest book Teaching to the North-East; Relationship-based learning in practice and also had the opportunity to discuss with him with him some of the key ideas in the book. The book represents an extension and deepening of the ideas he developed earlier in his career about the centrality of relationships for research and teaching, that were later put into practice in Te Kotahitanga and provides an approach to instructional practice that is designed to promote learning for every student including those currently marginalised from the benefits that education has to offer. Below, I explore some of the key ideas underpinning what Bishop calls ‘teaching to the north-east’.

Why relationships without effective pedagogy are not enough

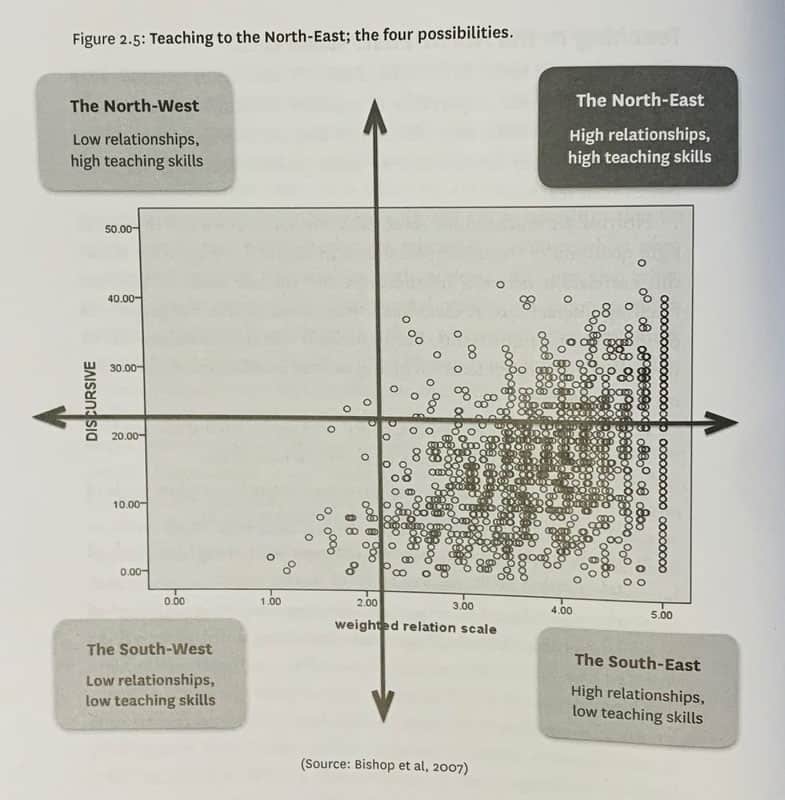

Central to Bishop’s thesis is that strong caring and learning relationships are an essential first step because they enable teachers to undertake the job of teaching effectively. However, relationships without an shift in pedagogy will not result in increased outcomes for students. The north-east (see image below) encapsulates this concept – those teachers that have both high relationships and high teaching skills are located within the North-East; these teachers are those who are able to support Maori and other marginalised students learning most effectively. Bishop suggests that over the past few decades in New Zealand, teachers have made important steps towards changing their theorising of students and rejecting deficit explanations for students’ learning difficulties. However, currently too few teachers are able to routinely implement the positive dialogic, interactive pedagogies that he considers are essential for bringing about changes in student outcomes. This problem is caused by teachers not being supported sufficiently to learn how to create effective caring and learning relationships in their classrooms as the base for effective teaching

For Bishop, culturally responsive pedagogies (CRP) too frequently are equated with a cultural competence approach. He suggests ‘to confuse CRP with a cultural competency approach is to expect teachers to learn about the culture of all their students – an impossible and really unnecessary task, for the students are already “experts” on how they see the world’. This does not mean that it’s not important for teachers to know and care for their students, to nurture their language and culture, or to see what students bring to learning environments as positive attributes to be built upon rather than deficiencies. But, according to Bishop, ‘too often culture is seen as tikanga or customs, and cultural iconography displayed in classrooms is seen as being sufficient for engaging marginalised students with learning’. Instead, Bishop suggests that a ‘responsive approach includes learners in their own determination and supports teachers to become even more professional and productive’.

Components of effective pedagogy

Teachers need to examine their theories of how students learn and know why they are implementing particular pedagogical approaches. Bishop suggests that the core elements of effective pedagogy are:

Teachers acting as leaders of learning by:

Creating an extended family-like context for learning,

Interacting within this context in ways we know support learners’ learning

Monitoring learners’ progress and the impact of the processes of learning on learning and modifying practices responsively.

Included among the dimensions of these three parts are the following;

- Creating a family-like context for learning and a well-managed learning environment

- Teachers holding and voicing high expectations for all their students

- Student knowing what they need to know and learn

- Ensuring that all new learning draws on prior knowledge and learning

- Embedding Assessment for learning across all lessons so that students know where they are at in their learning, what is working well and where they need to go next

- Including opportunities for co-construction and power-sharing

- Co-operative learning activities

- Utilising student-generated questions as a powerful means for deepening and extending the learning

- Utilising a narrative curriculum (using stories as a way for students to make sense of the world and to prompt new learning)

The importance of monitoring

Consistent monitoring of progress and impact is essential to the success of this approach. While monitoring will not of itself lead to improvement, it is impossible to know whether a school or teachers are improving without monitoring. As an approach, it involves monitoring of student voice, teachers engaging in goal setting and teaching students how to set goals for themselves, and teachers and leaders monitoring how changes in pedagogy are influencing different aspects of practice as well as student outcomes. A key way to enable monitoring to happen in schools is to formalise data conversations, with teachers and leaders coming together to discuss progress and improvement.

An instructional coaching approach

Research suggests that instructional coaching is one of the most effective forms of professional learning and it plays a central role in Bishop’s model of school improvement. It involves trained coaches (initially external experts who over time work to build internal capacity in the school) engaging in a series of observation and feedback cycles with teachers. It ultimately becomes a co-operative and collaborative model, where the coach-teacher relationship and ways of working closely mirror the co-operative learning approach teachers should build with their students.

Instructional leadership

From Te Kotahitanga Bishop learned that a focus on the classroom as the core nexus of change was not enough. It was essential to also address the core business of schools and to position principals and other school-level leaders as instructional leaders (or leaders of learning) in their school.

Many of the ideas discussed in Teaching to the North-East mirror findings from a range of other research studies. However, the book also raises a number of questions for me: What would it take to get this way of working into more schools? What role does the curriculum play alongside relationships and pedagogy in informing student learning and progress? How could instructional coaching become more commonplace in New Zealand schools? How could the links between the ideas in this book and the findings emerging from the science of learning research be explored? How do you encourage more teachers to recognise that their pedagogy might be lacking? How do we create better models of what these different elements actually look like in practice?