theteam@theeducationhub.org.nz

Postal Address

The Education Hub

110 Carlton Gore Road,

Newmarket,

Auckland 1023

Teachers’ expectations of their students’ learning may be more important in influencing student progress than pupils’ abilities. ‘High expectation teachers’ believe that students will learn faster and will improve their level of achievement. They also have more positive attitudes towards learners and more effective teaching practices. This paper outlines the key differences in teaching practices between low expectation and high expectation teachers. It provides helpful, practical teaching strategies to move towards high expectation and better teaching.

Teachers’ beliefs about their students and what they can achieve have a substantial impact on students’ learning and progress. Research shows that as well as expectations about individual students, teachers can be identified as having uniformly high or low expectations of an entire class of students. High expectation teachers believe that students will make accelerated, rather than normal, progress, and that pupils will move above their current level of performance (for example, from average to above average). Whereas, in general, low expectation teachers do not expect their students to make significant changes to their level of achievement over a year’s tuition. Studies show the effects of teacher expectations are pervasive. It seems it is not students’ ability that determines achievement, but rather their teachers’ expectations, and associated attitudes and practices. This is great news for teachers – you can make a difference.

Christine Rubie-Davies at the University of Auckland has investigated teacher expectations in New Zealand classrooms. Her research shows that teachers’ different levels of expectations lead to different instructional practices. For example, teachers with low expectations for students’ achievement may present less cognitively demanding experiences, spend more time reinforcing and repeating information, accept a lower standard of work, and emphasise rules and procedures. Low expectations set up a chain of low-level activities and, therefore, lower learning opportunities. When teachers’ expectations increase, their attitudes, beliefs, and teaching practices change. In general, high expectation teachers employ more effective teaching practices. When students are given more advanced opportunities to learn, they can make more progress.

The students of high expectation teachers show larger achievement gains, while the students of low expectation teachers make smaller or negative gains. The positive attitudes and equitable teaching practices of high expectation teachers also lead to higher levels of engagement, motivation and self-efficacy in students.

Research also shows that students are very aware of their teachers’ expectations for them. Students can provide examples that demonstrate a very subtle understanding of teacher attitudes, conveyed through words, tone and non-verbal communication. Students of teachers with low expectations come to view themselves more negatively, while students with high expectation teachers develop or maintain positive attitudes across the year, even when they have only made average progress. Positive attitudes to learning and about themselves as capable learners contribute to students’ greater achievement with high expectation teachers.

Teachers’ expectations for students lead them to deliver instruction in line with these expectations. For example, when teachers believe that low-achieving students are not capable of higher-level thinking, they provide differentiated learning experiences in their classes. Key areas of contrast between teachers with high expectations and teachers with low expectations include the quality of teaching statements, feedback, questioning and behaviour management.

| Low expectation teachers | High expectation teachers |

| Constantly remind students of procedures and routines. | Have procedures in place that students manage themselves. |

| Make more procedural and directional statements focused on students’ activities and behaviours, rather than on learning. For example, “Here is your reading book and worksheet for today. Off you go and read it and then do your worksheet.” | Make more statements focusing students’ attention on learning, or teaching new concepts, or relating current learning to prior activities and knowledge, or explaining and exploring concepts with students. For example, “This story is called … With that title, what do you think it is going to be about?” |

| Communicate details of the activities students have to complete. | Communicate learning intentions and success criteria with the class. |

| Ask predominantly closed questions based on facts. For example, “What’s the formula for finding area?” | Ask more open questions, designed to extend or enhance students’ thinking by requiring them to think more deeply. For example “And why do you say that? What clues in the story made you think that?” |

| Manage behaviour negatively and reactively. | Manage behaviour positively and proactively. |

| Make more negative statements about learning and behaviour. | Make more positive statements and create a positive class climate. |

| Set global goals for learning as a frame for planning teaching. | Set specific goals with students that are regularly reviewed and used for teaching and learning. |

| Take a directive role in planning the sequence of instruction and activities, and provide little opportunity for student choice. | Take a facilitative role and support students to make choices about their learning. |

| Link achievement to ability. | Link achievement to motivation, effort, and goal setting. |

| Use ability groupings and design different learning activities for each achievement group. | Encourage students to work with a variety of peers for positive peer modelling. |

| Provide lots of repetition in lower-level activities for low-ability children, and advanced activities for high-ability learners. | Provide less differentiation and allow all learners to engage in advanced activities. |

| Break learning down into incremental steps and organise learning in a linear fashion. | Undertake more assessment and monitoring so that students’ learning strategies can be adjusted when necessary. |

| Spend more time with low-achievers and give high achievers time to work independently. | Work with all students equally. |

| Give praise (or criticism) focused on accuracy. For example, “Well done. That’s right.” | Give specific, instructional feedback about students’ achievement in relation to learning goals. For example, “Nice addition, I like the way you have kept your numbers in straight columns so you didn’t get the tens and hundreds muddled.” |

| Respond to incorrect answers by telling student they are wrong and asking another student to respond. | Respond to incorrect answers by exploring the wrong answer, rephrasing explanations, or scaffolding the student to the correct answer. |

| Use incentives and rewards for motivation. | Base learning opportunities around students’ interests for motivation. |

Your teaching practices indicate your expectations of students. What do your practices reflect about your beliefs about your students and their ability to learn?

You ask open questions: Your students are encouraged to give their own ideas more often. You believe your students have good ideas to offer: high expectations.

You praise correct answers: You focus on performance, rather than the effort that goes into learning. Your students become performance-oriented (if they are high achievers) or develop performance-avoidance strategies if they have difficulties with the content, with negative consequences for motivation and engagement. Students are not supported to understand how they can improve: low expectations.

You do lots of formative assessment and your feedback develops learning: Your feedback is instructional with information about achievement and the next steps for learning, so that the student is enabled to make better learning decisions. For example, you might give a student a range of possible next steps, and say, “We could work on this or we could work on that, what would you like to work on?” Students are empowered and motivated to make progress in their learning, at exactly the moment that they are ready: high expectations.

You rephrase questions when answers are incorrect so that students are enabled to be successful, and to guide strategies for success: high expectations.

You use ability groupings to match instruction and activities to students’ differing learning needs: Your students are aware of differentiation and it has an effect on their motivation and their self-perceptions of achievement. Students have less freedom to make individual progress as they are constrained by the activities set for them: low expectations.

You extend high-achieving students with advanced activities and applications of skills and knowledge: Your students are aware of differentiation and it has an effect on their motivation and self-perceptions of achievement. It appears to the class that some students have more privilege or teacher esteem, because high achievers are trusted with some autonomy but low achievers are constrained to highly regulated teacher-set activities: low expectations.

You support low achievers by using a slower instructional pace, lots of repetition and review of prior learning. Low achievers’ progress is confined to the pace at which their learning is presented to them: low expectations.

You provide a range of learning activities and give students choice because you believe that if low achievers can become more motivated and engaged, their achievement will increase. You believe lack of achievement is due to a lack of motivation and effort, and not constrained by a lack of ability: high expectations.

You provide a clear framework for learning in terms of learning intentions and success criteria, so that students are cognitively and behaviourally engaged and can be trusted to manage their own learning: high expectations.

You set individual goals with students that are specific, regularly revisited and revised as students make progress. Student learning progresses at the individual student’s pace, rather than being constrained to a carefully planned progression implemented by the teacher, remaining focused on mastering one learning outcome until the entire group has achieved it. Individual learning goals help students get engaged in learning and intrinsically motivated, and help develop students’ independence: high expectations.

High expectations on their own are not enough to impact on achievement. It is the combination of high expectations with particular beliefs and teaching practices that have the biggest impact on student learning. In fact, the practices of high expectation teachers are those of well researched effective teaching practice.

Christine Rubie-Davies at the University of Auckland has demonstrated that when teachers adopt practices common to high expectation teachers (specifically relating to grouping and activities, class climate, and goal setting), there are gains to students’ achievement.

Here are some of these high expectation practices that will make the biggest difference to achievement.

Class climate

Goal setting

Examples of SMART goals for primary students:

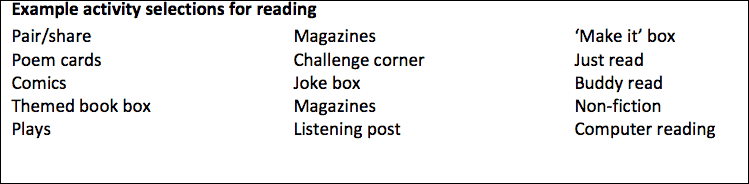

Shuffle name cards for random groupings, or agree groups at the beginning of the year based on students’ favourite colours or authors, their pets or other criteria such as alphabetical name order, birth month or shoe size. Create a clock spinner which can be used to randomly select which groupings will be used for that lesson’s activities.

Here are some aspects of your classroom teaching you might like to reflect upon in order to transform your expectations.

Is it time to examine your pedagogical beliefs, reset your expectations, and challenge yourself by implementing new teaching practices that will better serve all your students?

How often do you use the following high expectation practices in your teaching?

| Rarely | Sometimes | Regularly | |

| Ask open questions | |||

| Praise effort rather than correct answers | |||

| Use regular formative assessment | |||

| Rephrase questions when answers are incorrect | |||

| Use mixed-ability groupings | |||

| Change groupings regularly | |||

| Encourage students to work with a range of their peers | |||

| Provide a range of activities | |||

| Allow students to choose their own activities from a range of options | |||

| Make explicit learning intentions and success criteria | |||

| Allow students to contribute to success criteria | |||

| Give students responsibility for their learning | |||

| Get to know each student personally | |||

| Incorporate students’ interests into activities | |||

| Establish routines and procedures at the beginning of the school year | |||

| Work with students to set individual goals | |||

| Teach students about SMART goals | |||

| Regularly review goals with students | |||

| Link achievement to motivation, effort and goal setting | |||

| Minimise differentiation in activities between high and low achievers | |||

| Allow all learners to engage in advanced activities | |||

| Give specific, instructional feedback about students’ achievement in relation to learning goals | |||

| Take a facilitative role and support students to make choices about their learning | |||

| Manage behaviour positively and proactively | |||

| Work with all students equally |

Rubie-Davies, C. (2008). Expecting success: Teacher beliefs and practices that enhance student outcomes. Saarbrücken: Verlog Dr. Muller.

Rubie-Davies, C. (2014). Becoming a high expectation teacher: Raising the bar. Hoboken: Routledge.

By Dr Vicki Hargraves